Flea markets are a special kind of chaos: part treasure hunt, part time machine, part guessing game — with a side of “what the hell is this thing?” (Like it turns out to be a bed warmer, not a medieval pan.) Thankfully, this time I had someone smart with me to solve those mysteries.

Yesterday I scored. Three artworks in vintage frames. A green ceramic jar that’s will be working overtime to make my Berlin balcony feel vaguely Mediterranean. (A girl can dream, right?)

But here’s the real magic of flea markets: they’re not just about objects — they’re about other people’s lives, condensed into fragments. You don’t just buy a thing. You take home someone’s whisper of a life. The witnesses of past adventures and dramas. Bits of memory that can be reimagined, recontextualized, even reinvented.. And that, friends, is why artists have always loved them.

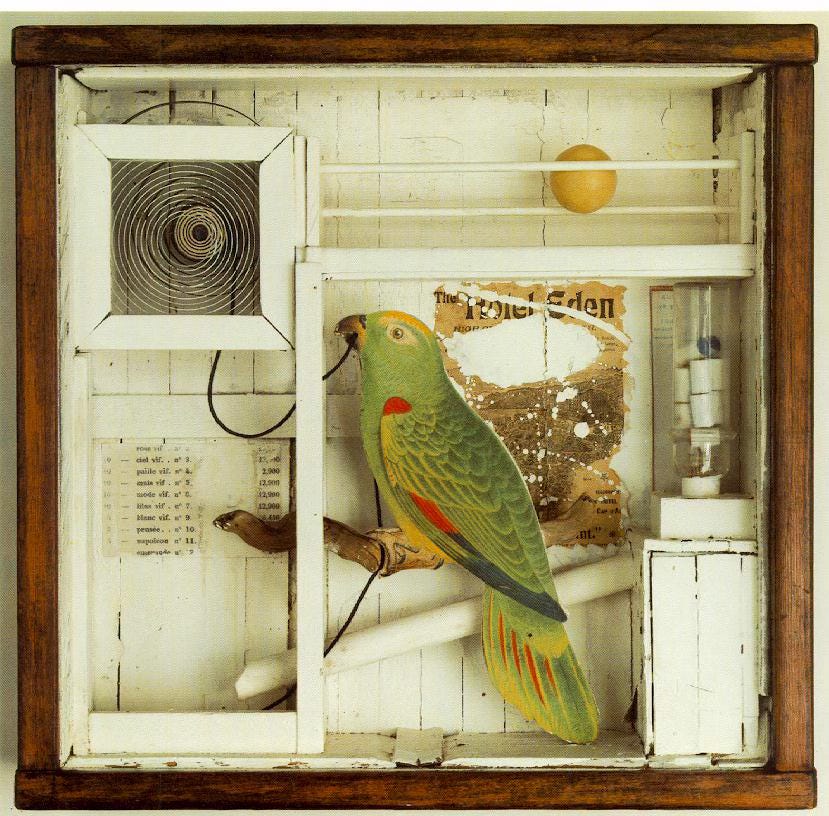

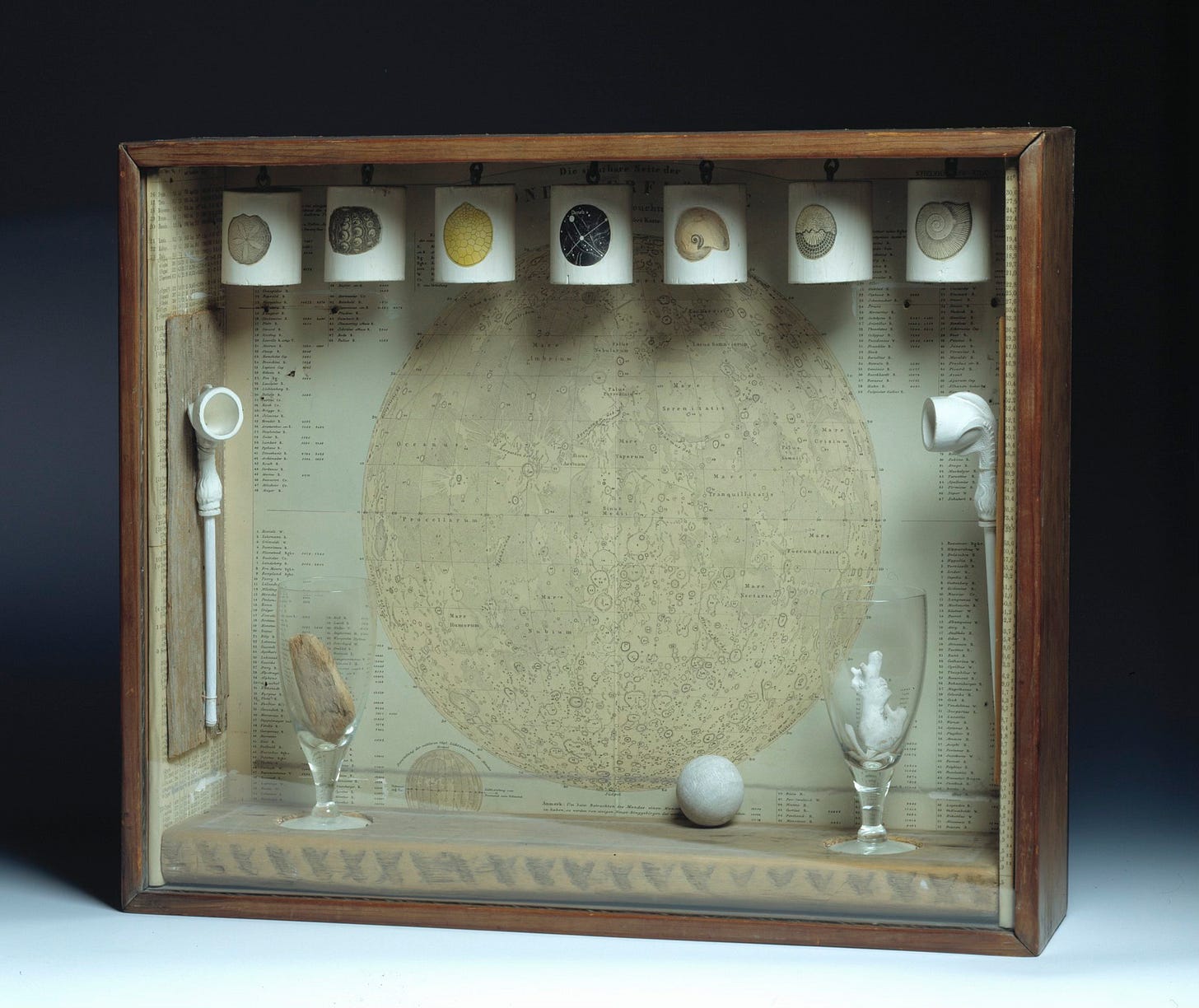

Joseph Cornell and His Shadow Boxes

Joseph Cornell didn’t just collect — he curated wonder. He lived with his mom and brother in Queens and rarely left New York, and never the U.S., but his imagination went everywhere. His preferred travel method? Junk bins, thrift shops, and flea markets.

Old marbles, ballerina photos, maps, bird feathers, star charts — he hoarded them all. But not as clutter. These relics became his iconic shadow boxes — dreamy little shrines arranged in wooden cases. Small theatres of lives.

Through the relics he found, Cornell built imaginary geographies, memories that never happened, and dream-worlds with passports made of found objects. His boxes are dreamlands — and proof that inspiration can come from the forgotten corners of someone else’s life. Note to myself: what dreamland would I build in a shadow box?

Louise Nevelson: The Queen of Assemblage

In 1961, MoMA hosted The Art of Assemblage, the first major show dedicated to this artform — the practice of taking found, discarded, broken, or random objects and turning them into sculpture. Often surreal, sometimes political, always layered. Always 3D.

Louise Nevelson was one of the earliest (and later, most recognised) artists of assemblage. Starting in the 1930s, she made her mark by turning the overlooked into the monumental. Her signature works were made entirely from discarded wood — chair legs, floorboards, furniture parts. She scavenged New York streets like a sculptural raccoon, then painted everything black, white, or gold, transforming it into vast architectural marvels like Sky Cathedral (1958).

And What About the Assemblages of Our Own Lives?

There’s something deeply voyeuristic — and oddly emotional — about walking through other people’s once-loved objects. It’s like archaeology laid out on a folding table. You’re not just shopping; you’re story-sniffing.

Which brings me back to my journey. Maybe decades from now, someone will pick up my green jar at a flea market and wonder: Who was she? What did she dream about?

So now I’m wondering: What parts of our homes might outlive us and end up in strangers’ lives? And if they do — what will they say about us? Our personalities? Our passions? Our weird habits and the way we care for things? Will they whisper something true — or something entirely invented?

And if Joseph Cornell made a shadow box about you today — just three objects from your life — what would be inside? Let’s start the game: You, in Three Objects: A Shadow Box Thought Experiment. Share yours in the comment below or head to subscriber chat on substack app. I’ll be sharing mine there!

This project is brushstroke by brushstroke. If you’d like to add one, support through a paid subscription — it keeps this canvas open for all.

Not ready to donate? ❤️ Tap the heart 💬 Drop a line in the comments 🔁 Re-stack or share with a curious friend 📸 Instagram works too. Thank you!