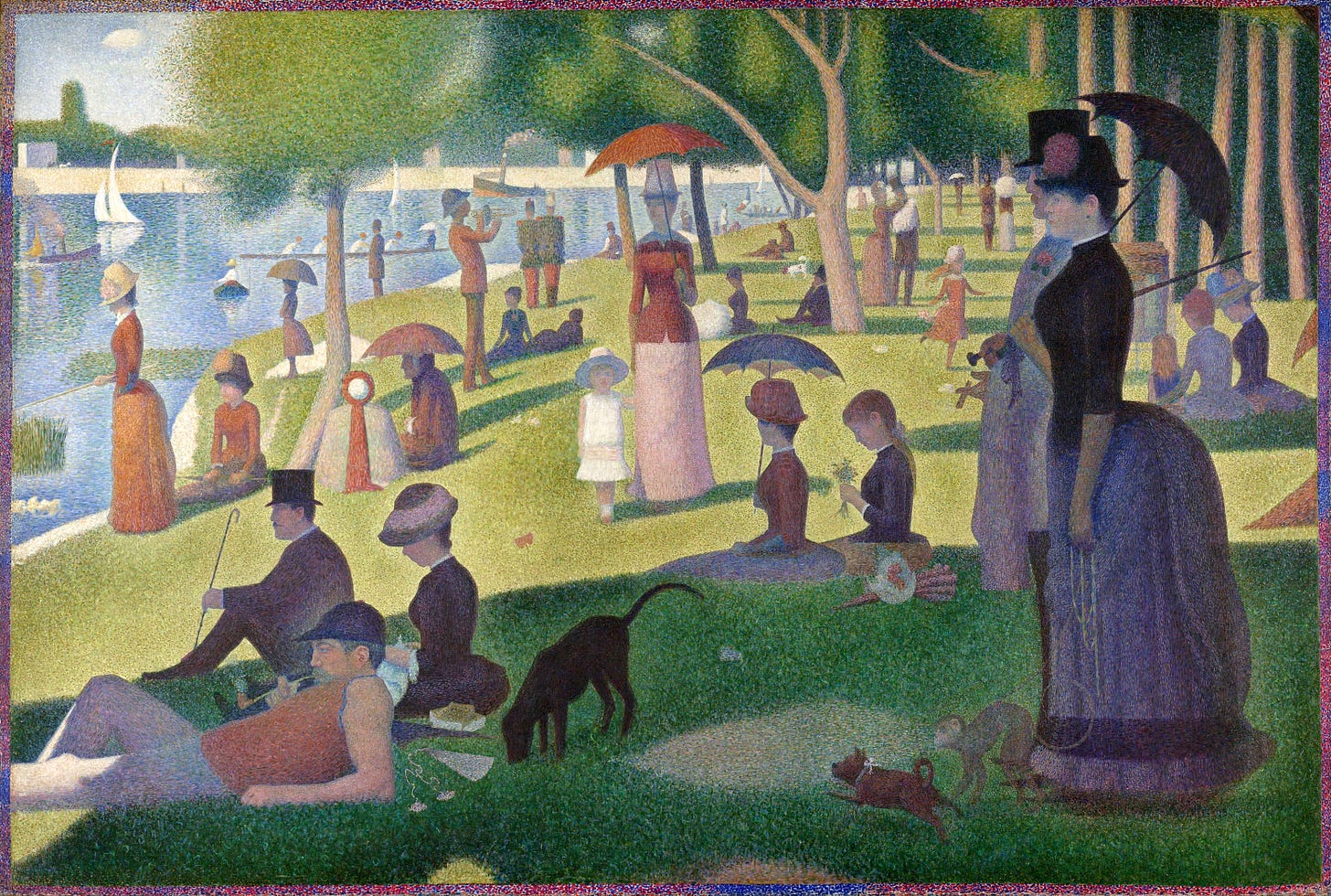

Imagine a cozy Parisian café in the late 19th century. Georges Seurat, the meticulous French painter, sits at a corner table, savoring his tarte au citron. The distinct layers of lemon zest cream and airy egg whites whipped with sugar meld into an intense burst of flavor. In his hand not occupied with a dessert fork, he holds an article by contemporary color theorists Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. Their optical studies propose that placing contrasting colors side by side makes them appear more vibrant to the human eye. Inspired, Seurat envisions a technique where individual dots of pure color, akin to distinct flavors, would blend in the viewer's eye to create a visual feast, instead of being premixed on the palette. This is a birth of Pointillism.

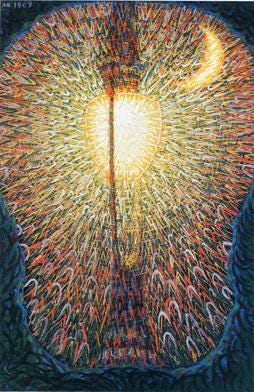

Down south in culinary Italy, inspired by Seurat, artists are cooking up their own visual recipe, which would be named Divisionism—a technique closely related to Pointillism but separating colors into individual strokes or patches, instead of purely focusing on dots. Giacomo Balla's Street Light exemplifies this approach, depicting a radiant electric street lamp that outshines a diminutive crescent moon, symbolizing the triumph of modernity over tradition.

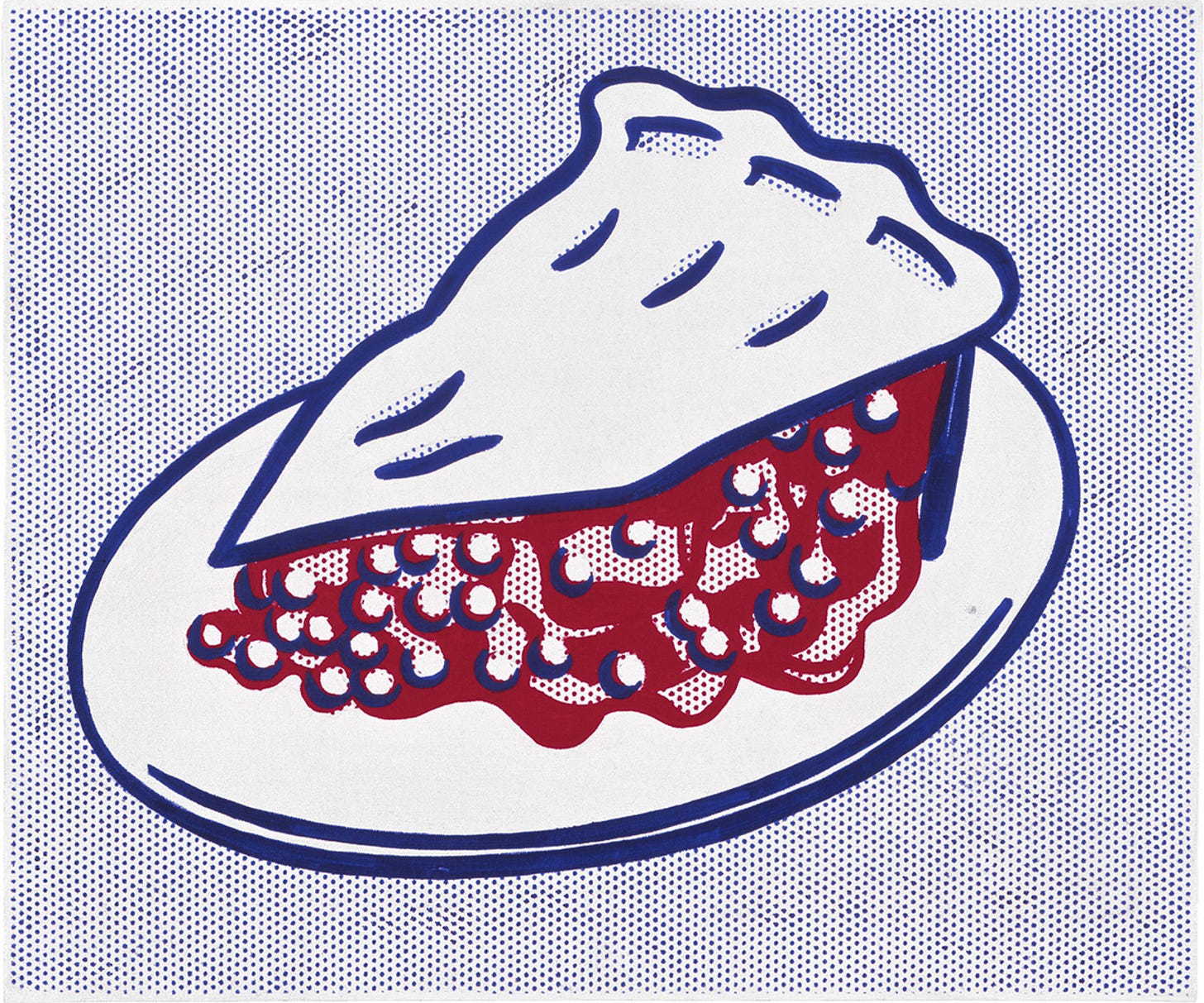

Fast forward to the 20th century, and the humble dot experienced a renaissance in the Pop Art movement. Taste Roy Lichtenstein, who transformed the Ben-Day dots—a printing technique using spaced dots to create shading—into monumental feasts. His iconic pieces parody mass media and commercial art, challenging the boundaries between high art and popular culture. Here is your Cherry pie!

Contemporary artists continue this dotty dialogue. Damien Hirst's "Spot Paintings," which number over a thousand since their inception in 1986, follow a meticulous system: uniform, machine-like but hand-painted grids, each dot boasting a distinct color and often named after pharmaceuticals, all aiming to evoke a sense of happiness—much like the satisfaction after a sweet treat (or pill?).

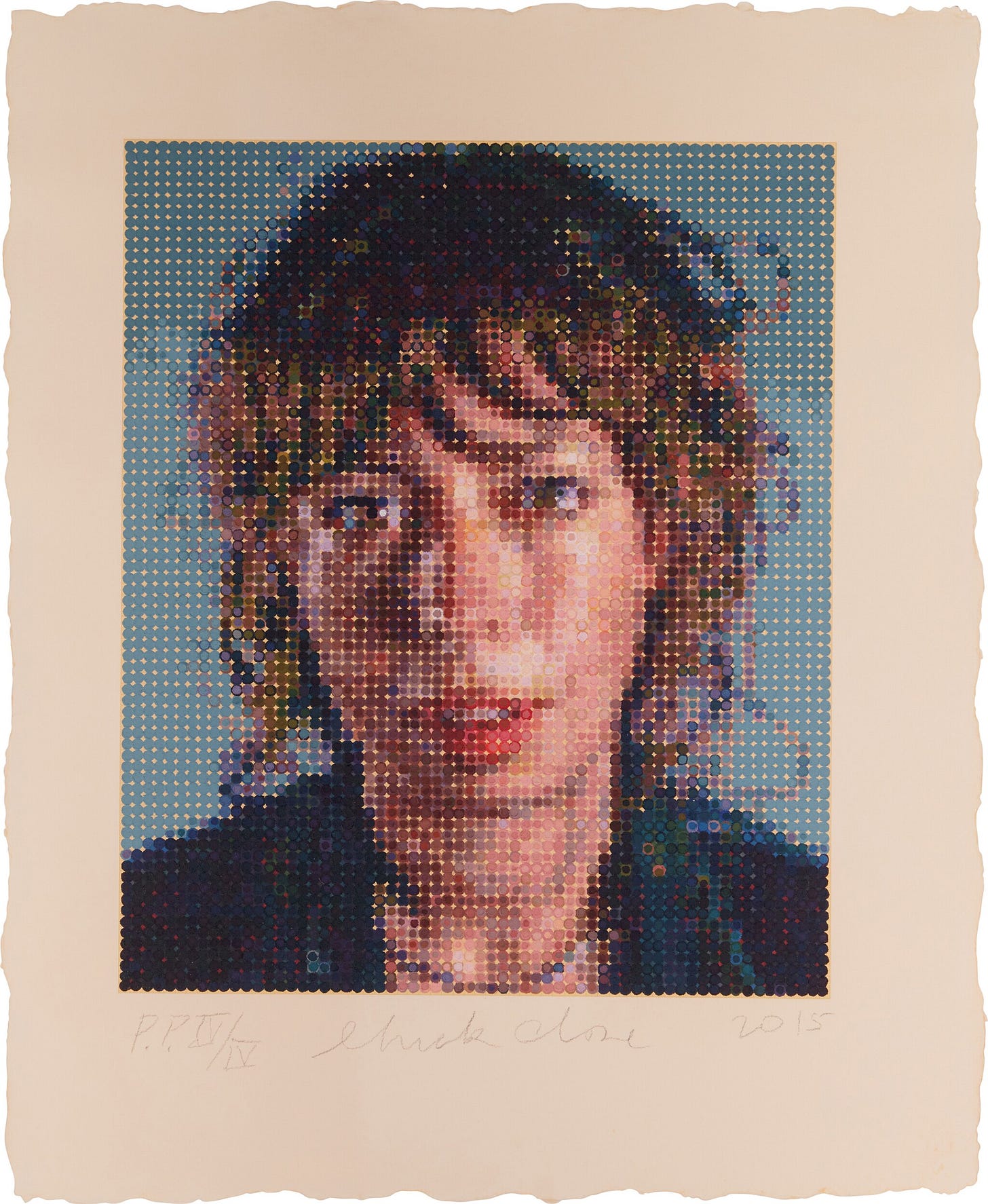

Chuck Close, on the other hand, employs a grid system of colored marks to craft large-scale, photorealistic portraits that, upon closer inspection, dissolve into abstract patterns. Both artists, in their unique ways, pay homage to the legacy of Pointillism and Divisionism, making a point that these techniques are timeless, just like the old good grandma’s recipes. Point.

Art needs more eyes — and so does this blog.

It’s free to read, but only grows if it travels.

Liked it even a bit? Tap the heart.

A line stuck with you? Drop it in a comment.

Smiled once? Hit restack.

Want to keep this writing alive? Send it to a curious friend to subscribe.